- Home

- Brad Graber

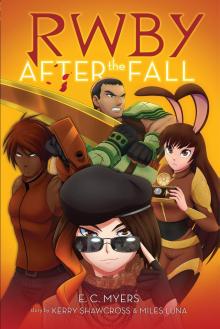

After the Fall Page 4

After the Fall Read online

Page 4

“But that was horrible,” Helen continued. “If it had been Barbra, we would have moved. Lenny would have insisted. But then Rikki doesn’t have a father? Barbra told me that Rikki’s mother never married. Such a shame. A girl should have a father. A man in her life.”

Rita took it all in. Helen’s attitude, body language, and tone. As she listened, she wondered where anyone got off judging her or her granddaughter. She was doing the best she could. She hadn’t expected to be raising a teenager at this time in life. Lord knows it tested the limit of her maternal skills, which had been severely challenged raising her own kids. The plan had been that, after Seymour, she’d remarry. Preferably a rich man. She’d be off somewhere traveling, enjoying the good life, instead of passing her days with the likes of women like Helen.

“Well, if you’ll excuse me, I have to get going,” Rita said, standing up, desperate to get away as her dryer approached the end of the spin cycle.

“But your wash?” Helen pointed at the dryer. “You haven’t taken your clothes out of the dryer yet.”

Rita blinked. “Yes, well, I just remembered. I have something in the oven. I better get it out. Then I’ll be right back down.”

Helen shook her head in disapproval. “It’s okay with me as long as I’m not waiting for that dryer.”

Rita offered a curt smile. You can drop dead for all I care, she thought, as she left the hot room.

◆

“I can’t remember her,” Rikki said, dish towel in hand, drying a dinner plate.

They stood together at the sink, Rita in a pair of yellow Playtex gloves washing, Rikki drying.

“It’s been years, and I still can’t remember.”

Rita gave Rikki a disapproving glance.

“Talk to me about El,” Rikki begged, while Rita squeezed more dishwashing soap onto the sponge. “Please, Rita.”

With her bright red hair slicked back, no makeup to cover her blotchy, pale skin, Rita looked every inch of her seventy-four years. Rikki wondered if she, too, might age like Rita. The mere thought gave her the shivers.

“You could never forget your mother,” Rita said as she pushed the suds around in the sink, scraping off bits of charred eggplant from the broiler pan. She’d tried to prepare the vegetable without frying. It was a trick shared by a coworker. Unfortunately, she’d failed to remember to spray the pan, and the eggplant stuck.

“But I can’t remember her,” Rikki insisted. “I don’t understand. Didn’t the doctor say that I’d eventually remember?”

“You were very sick, dear. Remember, you didn’t talk for three months.”

But Rikki didn’t remember. That was the whole point. “Yes, but that was then. I’m talking now.”

“But you’re well now,” Rita said, as she rinsed a dinner glass. “You’re in school. Good grades. Why do you want to talk about a time when you were ill?”

“I want to remember,” Rikki pressed. “I have to remember.”

“She loved you very much,” Rita stated, as if by describing Rikki’s mother’s affection it might fill Rikki’s void.

Rikki shook her head. “It’s good to hear, but that’s not the same as feeling the love yourself.”

Rita persisted. “Your mother used to say that nothing in the world would ever be as important to her as you. Nothing.” And then she gasped, bringing a soapy glove to her mouth to stifle a cry.

“Oh, Grandma,” Rikki said, a sweetness in her voice, as she put down the dishtowel. She rarely referred to Rita as Grandma, but during these moments, Rikki forgot the protocol. “Are you okay?” she asked, rubbing Rita’s back. “I didn’t mean to upset you.”

Rita shook her head and held onto the edge of the sink, leaning forward as the hot water from the tap continued to splash onto soiled silverware. “Forgive me,” she blurted out, as she struggled to pull herself together, tears flowing down her cheeks.

“Okay,” Rikki sighed, an arm about Rita, comforting the older woman. “We don’t have to talk about it. It’s okay.”

“I can’t,” Rita said, in an apologetic tone. She gasped for air between sobs. “It’s a horrible thing to lose a child . . . I don’t think I’ll ever . . . ever get over it. How could this terrible thing have happened?” She offered Rikki a pitiful look. “I wasn’t a perfect mother and I’m certainly not a perfect grandmother, but I didn’t deserve this,” she continued, shoulders slumped, chin pressed to her chest.

“No, of course not,” Rikki said.

When Rita finally looked up, Rikki used her dishtowel to wipe the soapsuds from her grandmother’s face.

“I’ll never recover. And I just can’t think about it.” Rita shook her head in defiance. “Such dreadful things shouldn’t ever happen.”

Rikki didn’t know what else to say. It had always been this way. Ever since she came to live with Rita. She couldn’t remember her mother, and Rita was unable to talk about El. And because they didn’t talk, Rikki feared she might never remember.

It was as if El had never been born.

Rikki removed her grandmother’s gloves. “Why don’t you go sit down and rest. I’ll finish up.”

“Are you sure?” Rita asked, eyes still glistening.

Rikki gave Rita’s arm a squeeze. “Yes, now go ahead.”

◆

Estelle Ida Goldenbaum had always hated her name.

Raised with girls named Susan, Lauren, Hope, and Linda, she couldn’t help feeling that the name Estelle was part of a much older generation of women named Fanny, Bertha, Irma, and Gertrude. So when Estelle had turned fifteen, she made a decision. She confronted her parents during dinner, and while her father poked at the broccoli on his plate, Estelle made her announcement. “I’m changing my name to El.” She glanced from one parent to the other. “El. E . . . L. It’s short and easy to spell.”

Her brother giggled.

Only two years younger, Rick was a slight, scrawny, blonde boy with thick glasses. “That’s what they call the elevated train in Chicago!” he cried out in delight, his eyes seeming even smaller in the heavy black frames.

Estelle closed her eyes and tried to ignore her brother.

“I was just reading about it in the library. The first stretch was 3½ miles and opened in June 1892. At first, it was powered by a steam engine, but then in 1893, the third-rail electrical power system was introduced . . .”

Dear God, she thought. Why does he have to be so darn smart?

“. . . at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition.”

“Rick . . . we’re eating. That’s enough,” Rita said with irritation.

When Estelle opened her eyes, her brother was looking up at her, a hurt expression plastered on his gentle face. His eyes seemed to be waiting for her response to the information he had offered. Instead, Estelle just shook her head, hoping he’d take the hint and stop talking. He did.

Her father, Seymour, offered a beleaguered look as if the difficulties of life had inflicted upon him a perpetual frown. He glanced over at Estelle’s mother. “Rita, what’s this all about?” The dark circles under his eyes seemed even more pronounced than usual.

Rita shrugged. She reached for a glass of water and took a sip.

“I’m serious,” Estelle whined. “My name is ridiculous. All the kids tease me. They’re calling me Essie. I hate it.”

“Estelle was my grandmother’s name,” her father said, focused intently on his daughter. “You don’t get to decide your name. That’s something that is given to you. Offered in love. Children don’t give back their names.”

“I don’t care what you say. It’s my life!” El shrieked as she jerked herself away from the table with such force that her water glass nearly tumbled over. “I’m tired of being Estelle.” She stood in defiance. “My name is El.”

“Sit back down,” Rita said in a firm tone, glaring at her daughter. “Where are your manners?”

Estelle defiantly stood behind her chair as if it were a shield. It all seemed so hopeless. The two adults bef

ore her would never understand. How could she ever get them to take her seriously?

“Sit down,” Rita again ordered as Estelle slinked back down into her seat.

Her father wiped his mouth with a napkin as he looked over at his daughter.

It seemed to Estelle that he was seeing her for the first time.

But even as he looked at her, he directed his comments to his wife. “Rita, I’ve had a long day. Can’t we have a quiet dinner?” His mouth settled back into its usual frown.

Rita glared across the table at her husband. “I’m sorry if this is all too much for you,” she said indignantly. “Seymour, you’re not the only one who works in this family. You should see the bunions on some of those women who come into the store. God. You’ve never seen such feet. And if you think being a mother, making dinner, and cleaning this apartment doesn’t entitle me to a little peace and quiet too—well—you’re wrong.”

Seymour took a breath. “I’m not having an argument. It’s already been a long day.”

Estelle shifted nervously in her seat. She hadn’t realized that her demand would bring on another family fight. All she wanted to do was change her name. Was that too much to ask?

Rita had one elbow on the table as she leaned forward. “I’m tired too, Seymour.”

“Tired?” her father snapped, his head slightly tilted to the right. “You’re tired? You drive fifteen minutes to Bayside to sell ladies’ shoes. I take the New York City bus and subway system to Manhattan . . . pushed and shoved through filth . . . to work a ten-hour day for an accounting firm that doesn’t even know my name.” Her father’s voice began to escalate. “They tell me I’m not up for a promotion because they want to recruit new talent.” He shook his head in disgust. “New talent . . . when I’ve given my life to that company.”

“Seymour,” Rita said, shaking her head, signaling that it was neither the time nor the place for his comments.

‘No,” Seymour answered. “It’s time she learned that she’s not the center of the universe. The world doesn’t revolve around her little blonde head.”

Rita reached for her pack of cigarettes.

“I wish you wouldn’t,” Seymour said. “It’s like kissing an ashtray.”

Rita lit up, taking a deep inhalation. She exhaled. “And since when are you interested in kissing?” she said in a dismissive manner.

Seymour pulled the napkin from his lap and tossed it on the table. “Fine,” he said, hands in the air. “I give up. You smoke,” he told his wife, “and you,” looking at his daughter, “can call yourself anything you want. As long as you’re both happy,” he said getting up from the table, “God knows, I’m not.”

◆

Harry stretched his neck. Why had he ever agreed to do a Microsoft Live Meeting with his editor?

The screen came to life as Edward Heaton flashed into view. In his mid-forties, Edward had a baby face. He’d often been mistaken for Neil Patrick Harris.

“Hey, Harry, how are you feeling?” Edward asked, a bright smile lighting up the screen.

“I’m fine,” Harry winced, adjusting himself in his seat. “My back’s a little stiff and I’ve been getting these terrific headaches.”

“Have you gone to the doctor yet?” Edward asked, expressing genuine concern.

“No,” Harry demurred. “You know I hate doctors. Almost as much as I hate editors.”

“Nice one, Harry,” Edward laughed. “After all these years of working together, I thought we were friends.”

“That depends,” Harry said, stroking the stubble on his chin. “Did you like the first three chapters?”

“Harry, it’s just too predictable. You’ve got to mix it up. The plot is too similar to the last book. No one wants to pay good money to read the same story.”

Harry shifted nervously. “Well, I think it’s good,” he said indignantly, faking an air of confidence. “I think it’s my best work yet.”

Edward peered into the screen, grimacing, cheeks pulled high, lips pressed tightly together. “Not quite,” he said. “Not by a long shot.”

“What happened to your glasses?” Harry asked.

Edward arched his brows. “I had laser surgery. I told you about it last week. I just did it yesterday.”

Harry nodded. He remembered. “And you’re back working so soon?”

“It didn’t hurt. It was one-two-three, done,” Edward said snapping his fingers.

“That’s the problem with the world today,” Harry muttered, mostly to himself.

Edward leaned in closer to the screen. His nose, beautifully straight and well-proportioned for his face, became a projectile as if reflected by a fun-house mirror. “What did you say? I can’t hear you.”

“See,” Harry blasted. “You’re leaning in, thinking you’ll be able to hear me better. You stupid bastard. You can’t hear me any better. I’m not there.”

“Oh, Harry,” Edward reproached him. “Is this about those chapters?”

Harry pounded on his desk with his fist. “Everything is about those chapters.”

“Now, don’t lose your temper,” Edward advised. “We’ve done this before. Just start again. And this time, pull the reader in quicker. You write murder mysteries. That’s your genre. That’s what sells. And it’s like I always say . . .”

Harry completed the sentence: “. . . if you write for your readers, you’ll have a best-seller. I know.”

“Especially when they’re eagerly awaiting your next book.”

Harry nodded, dejected. “Yes, I mustn’t disappoint my audience. I get it.”

“Good,” Edward said. “I’ll check back with you next week. Give Beetle a treat from me.”

Harry turned to the terrier curled up in his dog bed, fast asleep. “Beetle just gave you the finger,” Harry said, holding his middle finger up to the screen.

“Nice,” Edward laughed. “So glad you can take constructive criticism. Why not use all that anger in your writing? It’ll make those scenes jump right off the page.”

◆

Rikki turned the corner and walked past the Chinese laundry, the dry cleaner, the candy store, and the barbershop. The eight-story building where she lived with Rita came into view. Terraces painted an aqua blue contrasted sharply with the red brick. Aguilar Gardens—an odd name, considering there were no flowers, just a contiguous cement walkway bordered by a chain-link fence and 3×5 Keep Off the Grass signs posted every twenty feet to guard a strip of greenery that bordered the building.

A raspy voice called out as Rikki approached the front steps. “Rikki, how’s your grandmother feeling?”

Rikki winced.

It was Mrs. Mandelbaum from 6G. Her apartment was right across from the elevator on Rikki’s floor. The old woman often popped her head out, surprising Rikki as she waited for the elevator. “That Mrs. M is such a yenta,” Rita had warned Rikki. “Be careful about being too friendly. Not everyone needs to know our business.”

Despite the chilly weather, Mrs. M had set up a folding chair on the sidewalk, amid the crowd of other seniors. As the old woman sat with her legs crossed, Rikki could see her pink and green housedress, paired with a blue winter peacoat. Her white hair, clipped short in a boyish cut, exposed tiny, bat-like ears. Rikki imagined those ears in a 360-degree rotation as Mrs. M clocked the arrival and departure of everyone on the sixth floor, distinguishing tenants by their footsteps. Twenty steps. The Millers in 6D. Forty steps. The Greens in 6M.

“I haven’t seen her since yesterday,” the yenta said, as if she was in charge of attendance at Aguilar Gardens. “Is she okay? Do I need to stop by and check on her?”

Rikki tried to keep a poker face. The mere prospect of Mrs. M entering the apartment and snooping around was abhorrent. “Oh, no. She’s fine,” she reassured the older woman.

Rikki hated living in the high-rise. Except in the dead of winter, seniors congregated at the front of the building to pass the time, mostly gossiping, and, according to Rita, annoying their neighbors. So

me brought their own folding chairs, like Mrs. M, while others just milled about, leaning against the handrails, and in warmer weather sitting on the steps, blocking access to the front door. They seemed to know, or appeared entitled to know, everyone else’s business.

And they weren’t only out front.

They were in the lobby, the laundry room, and on the benches out back by the cement playground. Milling around, asking questions, prying with their eyes. Wondering how Rikki was doing in school, where she was coming from, where she was going. A million questions. Sharp tones, demanding voices, probing Rikki and Rita’s personal business out on the street for everyone to hear.

“Rita’s fine,” she answered, knowing it was a difficult day for her grandmother, but hoping to end the questioning.

The group of adults turned their attention to Rikki. Dull eyes fired, imaginations blossomed, as Rikki sensed judgments being formed. She wanted to stab Mrs. M with her Bic pen, but then the Bic was her favorite and she saw no reason to sacrifice a perfectly good pen for the likes of Mrs. M.

The truth was that Rita had taken to her bed. It happened every year on El’s birthday. Rita became inconsolable. And though Rikki, too, felt upset, her reasons were different. She didn’t suffer the physical collapse that Rita endured. How could she, when she remembered nothing of her mother? Still, she was certain that she must have loved her mother very much. Hadn’t she been hospitalized for three months? Didn’t she have to regularly see a psychiatrist? And yet, when Rita fell apart, Rikki found herself distracted. Frightened by the intensity of the older woman’s grief.

“Then why haven’t I seen her?” Mrs. M continued to push.

Rikki started to make her way past. “I can’t really say,” she admitted, “but she’s absolutely fine.”

Mrs. M wasn’t quite through. “Are you sure, dear? The flu is going around. How are you feeling? You don’t look well.”

All eyes again turned on Rikki.

“I feel very well, Mrs. Mandelbaum,” she boldly answered, looking from one adult to the other. “Perhaps you shouldn’t be sitting out here in the cold. It is November. And you’re not a young woman,” Rikki blurted out as she rushed up the steps, desperate to get away.

After the Fall

After the Fall